ASPCA4EVER

Well-Known Member

The Radiation Boom

Radiation Offers New Cures, and Ways to Do Harm

By WALT BOGDANICH

Published: January 23, 2010

As Scott Jerome-Parks lay dying, he clung to this wish: that his fatal radiation overdose — which left him deaf, struggling to see, unable to swallow, burned, with his teeth falling out, with ulcers in his mouth and throat, nauseated, in severe pain and finally unable to breathe — be studied and talked about publicly so that others might not have to live his nightmare.

Scott Jerome-Parks, with his wife, Carmen, was 43 when he died in 2007 from a radiation overdose. More Photos »

The Radiation Boom

When Treatment Goes Awry This is the first in a series of articles that will examine issues arising from the increasing use of medical radiation and the new technologies that deliver it.

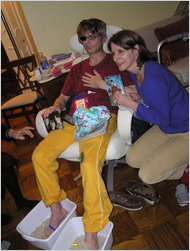

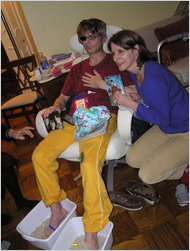

For his last Christmas, Mr. Jerome-Parks rested his feet in buckets of sand his friends had sent from a childhood beach. More Photos >

Sensing death was near, Mr. Jerome-Parks summoned his family for a final Christmas. His friends sent two buckets of sand from the beach where they had played as children so he could touch it, feel it and remember better days.

Mr. Jerome-Parks died several weeks later in 2007. He was 43.

A New York City hospital treating him for tongue cancer had failed to detect a computer error that directed a linear accelerator to blast his brain stem and neck with errant beams of radiation. Not once, but on three consecutive days.

Soon after the accident, at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan, state health officials cautioned hospitals to be extra careful with linear accelerators, machines that generate beams of high-energy radiation.

But on the day of the warning, at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, a 32-year-old breast cancer patient named Alexandra Jn-Charles absorbed the first of 27 days of radiation overdoses, each three times the prescribed amount. A linear accelerator with a missing filter would burn a hole in her chest, leaving a gaping wound so painful that this mother of two young children considered suicide.

Ms. Jn-Charles and Mr. Jerome-Parks died a month apart. Both experienced the wonders and the brutality of radiation. It helped diagnose and treat their disease. It also inflicted unspeakable pain.

Yet while Mr. Jerome-Parks had hoped that others might learn from his misfortune, the details of his case — and Ms. Jn-Charles’s — have until now been shielded from public view by the government, doctors and the hospital.

Americans today receive far more medical radiation than ever before. The average lifetime dose of diagnostic radiation has increased sevenfold since 1980, and more than half of all cancer patients receive radiation therapy. Without a doubt, radiation saves countless lives, and serious accidents are rare.

But patients often know little about the harm that can result when safety rules are violated and ever more powerful and technologically complex machines go awry. To better understand those risks, The New York Times examined thousands of pages of public and private records and interviewed physicians, medical physicists, researchers and government regulators.

The Times found that while this new technology allows doctors to more accurately attack tumors and reduce certain mistakes, its complexity has created new avenues for error — through software flaws, faulty programming, poor safety procedures or inadequate staffing and training. When those errors occur, they can be crippling.

“Linear accelerators and treatment planning are enormously more complex than 20 years ago,” said Dr. Howard I. Amols, chief of clinical physics at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York. But hospitals, he said, are often too trusting of the new computer systems and software, relying on them as if they had been tested over time, when in fact they have not.

Regulators and researchers can only guess how often radiotherapy accidents occur. With no single agency overseeing medical radiation, there is no central clearinghouse of cases. Accidents are chronically underreported, records show, and some states do not require that they be reported at all.

In June, The Times reported that a Philadelphia hospital gave the wrong radiation dose to more than 90 patients with prostate cancer — and then kept quiet about it. In 2005, a Florida hospital disclosed that 77 brain cancer patients had received 50 percent more radiation than prescribed because one of the most powerful — and supposedly precise — linear accelerators had been programmed incorrectly for nearly a year.

Dr. John J. Feldmeier, a radiation oncologist at the University of Toledo and a leading authority on the treatment of radiation injuries, estimates that 1 in 20 patients will suffer injuries.

Most are normal complications from radiation, not mistakes, Dr. Feldmeier said. But in some cases the line between the two is uncertain and a source of continuing debate.

“My suspicion is that maybe half of the accidents we don’t know about,” said Dr. Fred A. Mettler Jr., who has investigated radiation accidents around the world and has written books on medical radiation.

Identifying radiation injuries can be difficult. Organ damage and radiation-induced cancer might not surface for years or decades, while underdosing is difficult to detect because there is no injury. For these reasons, radiation mishaps seldom result in lawsuits, a barometer of potential problems within an industry.

In 2009, the nation’s largest wound care company treated 3,000 radiation injuries, most of them serious enough to require treatment in hyperbaric oxygen chambers, which use pure, pressurized oxygen to promote healing, said Jeff Nelson, president and chief executive of the company, Diversified Clinical Services.

While the worst accidents can be devastating, most radiation therapy “is very good,” Dr. Mettler said. “And while there are accidents, you wouldn’t want to scare people to death where they don’t get needed radiation therapy.”

<story source>

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/24/health/24radiation.html?th&emc=th

*******************************************************

So when in doubt and we the consumer don't know precisely what to ask...will the hospital tell us the truth when we ask: have these technicians been certified on this equipment, have you ever had a patient get to much/suffer a mis-aimed pointed beam, died from the treatment instead of the disease? Will the cancer treatment centers be honest...do they have to report the injuries/deaths/mistakes

Radiation Offers New Cures, and Ways to Do Harm

By WALT BOGDANICH

Published: January 23, 2010

As Scott Jerome-Parks lay dying, he clung to this wish: that his fatal radiation overdose — which left him deaf, struggling to see, unable to swallow, burned, with his teeth falling out, with ulcers in his mouth and throat, nauseated, in severe pain and finally unable to breathe — be studied and talked about publicly so that others might not have to live his nightmare.

Scott Jerome-Parks, with his wife, Carmen, was 43 when he died in 2007 from a radiation overdose. More Photos »

The Radiation Boom

When Treatment Goes Awry This is the first in a series of articles that will examine issues arising from the increasing use of medical radiation and the new technologies that deliver it.

For his last Christmas, Mr. Jerome-Parks rested his feet in buckets of sand his friends had sent from a childhood beach. More Photos >

Sensing death was near, Mr. Jerome-Parks summoned his family for a final Christmas. His friends sent two buckets of sand from the beach where they had played as children so he could touch it, feel it and remember better days.

Mr. Jerome-Parks died several weeks later in 2007. He was 43.

A New York City hospital treating him for tongue cancer had failed to detect a computer error that directed a linear accelerator to blast his brain stem and neck with errant beams of radiation. Not once, but on three consecutive days.

Soon after the accident, at St. Vincent’s Hospital in Manhattan, state health officials cautioned hospitals to be extra careful with linear accelerators, machines that generate beams of high-energy radiation.

But on the day of the warning, at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn, a 32-year-old breast cancer patient named Alexandra Jn-Charles absorbed the first of 27 days of radiation overdoses, each three times the prescribed amount. A linear accelerator with a missing filter would burn a hole in her chest, leaving a gaping wound so painful that this mother of two young children considered suicide.

Ms. Jn-Charles and Mr. Jerome-Parks died a month apart. Both experienced the wonders and the brutality of radiation. It helped diagnose and treat their disease. It also inflicted unspeakable pain.

Yet while Mr. Jerome-Parks had hoped that others might learn from his misfortune, the details of his case — and Ms. Jn-Charles’s — have until now been shielded from public view by the government, doctors and the hospital.

Americans today receive far more medical radiation than ever before. The average lifetime dose of diagnostic radiation has increased sevenfold since 1980, and more than half of all cancer patients receive radiation therapy. Without a doubt, radiation saves countless lives, and serious accidents are rare.

But patients often know little about the harm that can result when safety rules are violated and ever more powerful and technologically complex machines go awry. To better understand those risks, The New York Times examined thousands of pages of public and private records and interviewed physicians, medical physicists, researchers and government regulators.

The Times found that while this new technology allows doctors to more accurately attack tumors and reduce certain mistakes, its complexity has created new avenues for error — through software flaws, faulty programming, poor safety procedures or inadequate staffing and training. When those errors occur, they can be crippling.

“Linear accelerators and treatment planning are enormously more complex than 20 years ago,” said Dr. Howard I. Amols, chief of clinical physics at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York. But hospitals, he said, are often too trusting of the new computer systems and software, relying on them as if they had been tested over time, when in fact they have not.

Regulators and researchers can only guess how often radiotherapy accidents occur. With no single agency overseeing medical radiation, there is no central clearinghouse of cases. Accidents are chronically underreported, records show, and some states do not require that they be reported at all.

In June, The Times reported that a Philadelphia hospital gave the wrong radiation dose to more than 90 patients with prostate cancer — and then kept quiet about it. In 2005, a Florida hospital disclosed that 77 brain cancer patients had received 50 percent more radiation than prescribed because one of the most powerful — and supposedly precise — linear accelerators had been programmed incorrectly for nearly a year.

Dr. John J. Feldmeier, a radiation oncologist at the University of Toledo and a leading authority on the treatment of radiation injuries, estimates that 1 in 20 patients will suffer injuries.

Most are normal complications from radiation, not mistakes, Dr. Feldmeier said. But in some cases the line between the two is uncertain and a source of continuing debate.

“My suspicion is that maybe half of the accidents we don’t know about,” said Dr. Fred A. Mettler Jr., who has investigated radiation accidents around the world and has written books on medical radiation.

Identifying radiation injuries can be difficult. Organ damage and radiation-induced cancer might not surface for years or decades, while underdosing is difficult to detect because there is no injury. For these reasons, radiation mishaps seldom result in lawsuits, a barometer of potential problems within an industry.

In 2009, the nation’s largest wound care company treated 3,000 radiation injuries, most of them serious enough to require treatment in hyperbaric oxygen chambers, which use pure, pressurized oxygen to promote healing, said Jeff Nelson, president and chief executive of the company, Diversified Clinical Services.

While the worst accidents can be devastating, most radiation therapy “is very good,” Dr. Mettler said. “And while there are accidents, you wouldn’t want to scare people to death where they don’t get needed radiation therapy.”

<story source>

http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/24/health/24radiation.html?th&emc=th

*******************************************************

So when in doubt and we the consumer don't know precisely what to ask...will the hospital tell us the truth when we ask: have these technicians been certified on this equipment, have you ever had a patient get to much/suffer a mis-aimed pointed beam, died from the treatment instead of the disease? Will the cancer treatment centers be honest...do they have to report the injuries/deaths/mistakes